When Angolan filmmakers Fradique (a.k.a. Mario Bastos) and Hugo Salvaterra, a NYFA Fulbright student, met in high school, little did they know it would be the beginning of a friendship and collaboration that would continue into adulthood, where they would both be studying at the New York Film Academy, and take them to the prestigious We Are One: A Global Film Festival. Created by the Tribeca Film Festival as a fundraiser for organizations addressing the world’s COVID-19 crisis, We Are One includes selections from top festivals such as Cannes, Berlin, Venice, and Rotterdam.

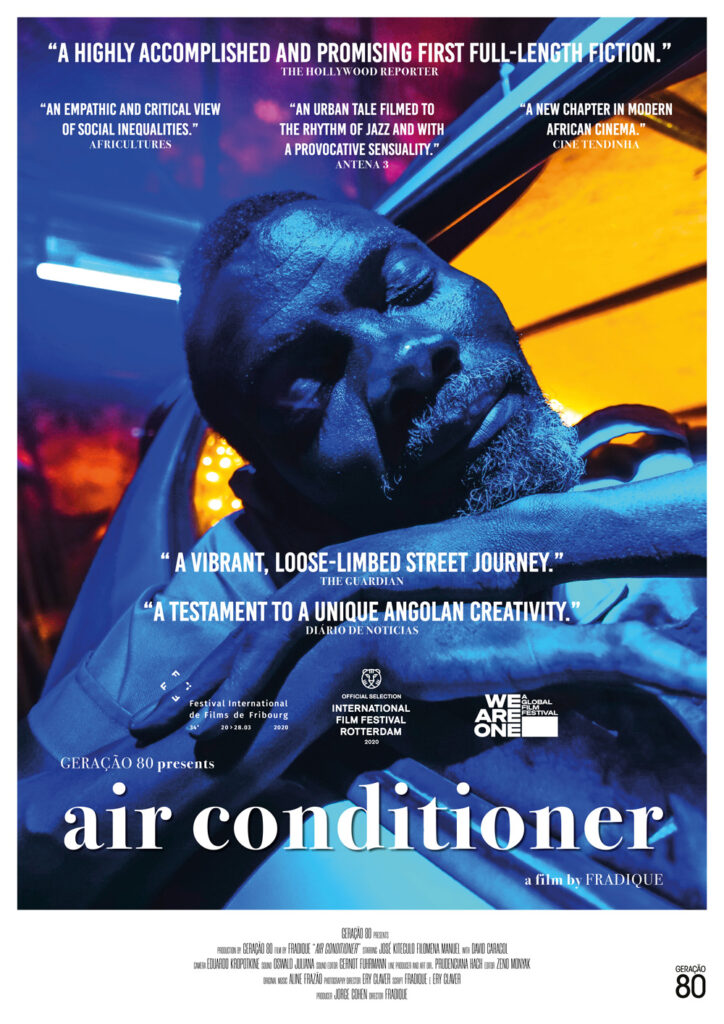

Air Conditioner, Fradique’s first fictional feature as writer and director, will premiere on YouTube on Saturday, June 6, 2020, at 11:45 am Eastern. It will then become available on demand for seven days afterwards. Attending the premiere is free, but donations are welcome.

Crickett Rumley, NYFA’s Director of Film Festivals, caught up with Fradique and Hugo right before the festival and asked them about their experiences.

Rumley: Congratulations on this amazing success. Fradique, could you tell us more about Air Conditioner and how it came to be?

Fradique: This is actually a project that I had started writing a couple of years ago while I was developing what was supposed to be my first fiction film, The Kingdom of Casuarinas. Air Conditioner was kind of a side project that eventually ended up becoming my first fiction film, which for me was a big lesson on how in our line of work these things take many years. Sometimes the next one is not the one you thought it would be. The film was written by me and the director of photography, Ery Claver, who is a very talented filmmaker and someone that sees cinema as I do.

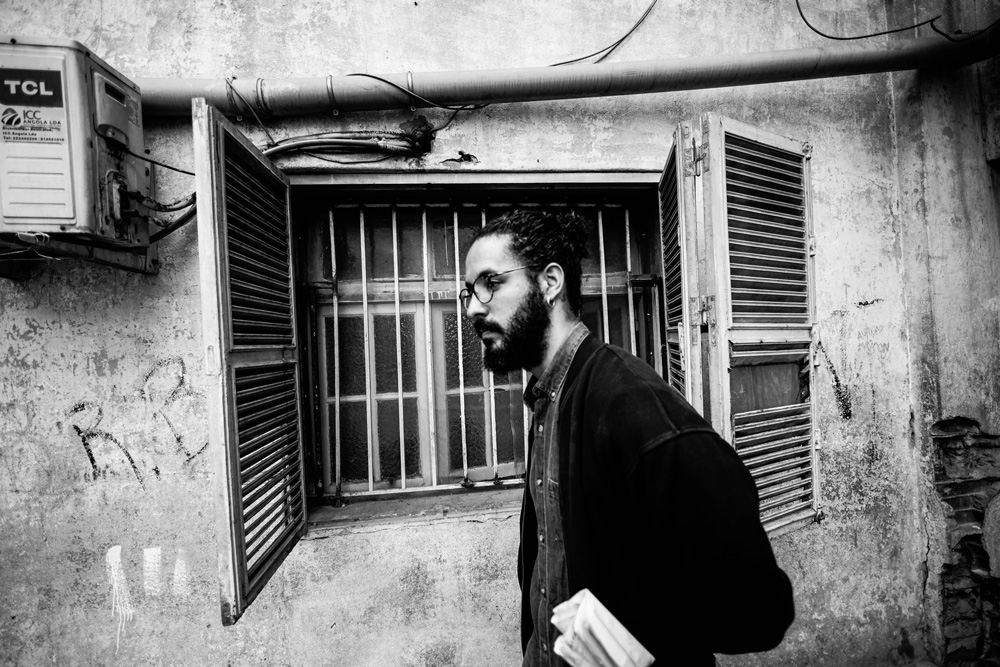

Air Conditioner is a magic neo-realistic journey through downtown Luanda, Angola, where we follow Matacedo, a security guard of an old building, while he tries to retrieve his boss’s AC in a city where all the AC’s are falling. This is a film about loss, how we live together as society, and a critique of social classes in a city that is past-present-future. My biggest inspiration for this film was my own life experience growing up and living in many different buildings in downtown Luanda and also the idea that these invisible workers that are the heart and soul of our city should be main characters on the stories we watch on the big screen.

Rumley: What was the most challenging thing about making the film? What did you learn in the process?

Fradique: The film was produced and shot with a very small crew, almost guerrilla-style, so letting go and accepting what surroundings are offering you was my biggest challenge and lesson. Usually in all my projects, I try to be as meticulous as I can regarding the script, storyboard, and shooting plan, but with this film we wanted to work not only with non-actors, but also with the real location where the story takes place, the building. In the end, the film resulted from creative acts derived from a deep structure. It privileges character and location over traditional narrative. The improvisation in this project was not simply a free flow of expression, but a rigorous and disciplined act of playing from a given structure at its core. I believe that this mixture was essential to bring some raw and poetic experiences to the screen while pushing at the same time stronger performances from the cast.

Rumley: The film premiered at Rotterdam, which is an amazing place to launch. What was that experience like?

Fradique: Yes, the film had its World Premiere at the Rotterdam International Film Festival in the section of ‘Bright Future Main Program’ in 2020. For me, it was an honor to have the first festival screening at IFFR. It was my second time over there and I love and stand for everything that the festival believes. A lot of filmmakers that inspire me have been at IFFR; it’s a great home for the global south cinema. The feedback after the screenings exceeded my expectations, which were very low because I was very tired after a year of working on the film. We had five screenings and they were all sold out before the festival even started. The audience in Rotterdam are very generous and authentic cinephiles. We had great reviews at The Hollywood Reporter, The Guardian, and other local newspapers. The original soundtrack, which was composed by Aline Frazão for the film, was one of the elements that reviewers and the audiences mention a lot. She did an incredible job, and I believe the music in the film brought to the surface the soul of the main character, Matacedo, as well the city of Luanda.

Rumley: Fradique and Hugo, what are you each looking forward to with the film’s screening at We Are One?

Fradique: How this festival was put together still amazes me. We Are One offers a global audience easy access to great films and conversations about filmmaking. It’s free, yet it’s also open to donations to fight against Covid-19. For me as a filmmaker in the current crisis that was an important criterion to join this initiative because it has bigger concerns than defending a particular festival or film. It shows how important it is to work and act collectively. We are all still learning and trying to figure out what the future of independent cinema and festivals will be, but it’s important to try new formats and be open. I hope at the festival Air Conditioner reaches audiences that probably were not going to watch this film or simply give someone who is at home a small pleasant journey to Luanda, Angola.

Hugo: Personally, I’m mostly proud of the company’s achievement, amazed at the scale and sheer diversity of the festival. After attending many festivals like Tribeca, LA and NY film festivals or even the Venice Biennale, this feels like the most diverse and representative curatorship I’ve seen thus far. It truly represents cinema and independent cinema as a planetary global experience. It also gives me added hope that the usually non-English, non-western filmmaking voices can also be heard on a global scale for a more democratic and inclusive future for all independent filmmakers.

Rumley: Let’s backtrack for a minute to the beginnings of your collaboration. How did you meet and start working together? Was it attending NYFA, or back at home?

Fradique: I met Hugo while I was still in high school here in Angola. Afterwards we went to study abroad. He went to Europe, and I went to the US in 2004 where I did NYFA’s 1-Year Filmmaking program and also a BFA at the Academy of Art in San Francisco. Once I got back to Angola in 2010, I started a production company called Geração 80, with Jorge Cohen and Tchiloia Lara. Hugo was one of the first artists to come on board at Geração 80. Our production company will celebrate 10 years this year.

Hugo: I met Fradique in the cocoon of our high school here in Luanda, Angola, in our youth. If my memory doesn’t fail me, I think I formed a kinship with him when I was still in university in Lisbon making music on the side. He showed some interest in shooting a video for a small EP I had made in my bedroom, something I never expected, and it meant a lot at the time. Our connection really took off when I joined Geração 80. I did my first job for the company while I was living in London in the end of 2011 then joined in early 2012, way before NYFA. I was still an aspiring filmmaker, writing film reviews and working mostly with photography. A memorable day is when I first made it into his bedroom, shortly after arriving from London. Large sections of his DVD film collection mirrored mine. That’s when I realized that more than a friend, I had found a brother through our shared passion for film.

Rumley: Hugo, what was your position on ‘Air Conditioner?’

Hugo: I was fresh from returning to Angola post-NYFA and figuring out how to promote my film “1999” here in Luanda. In an independent production company, a lot of sacrifices have to be made in order to make things happen. So I was focused on the commercial end of the company making sure that my colleagues could enjoy the freedom and necessary focus to produce and shoot the film.

Rumley: Your production company sounds really interesting. Can you describe it, how you work, what you do, how you started it?

Fradique: We will celebrate a decade next month. We started only with three people, and today we are a group of eighteen professionals working in the audiovisual industry in Angola. At the beginning the goal was to just make cinema, but soon we realized that we had to do other work to survive. In Angola there’s no film funds or initiatives, so being able to put together a production company that does not only cinema, but commercial and corporate work gave us the resources to be able to build a great team and acquire top equipment to make us more independent. Over the last ten years, we produced one feature fiction film, four feature-length documentaries, six short films and worked on a couple of international co-productions. When it comes to producing our films, we work very much like a collective. Everyone works on each other’s projects, and we only finish a film when it reaches an audience. We don’t make films to be put into drawers, we believe independent/author cinema should meet bigger audiences as well. We are tired of seeing our film theaters only with Hollywood films. We want not only more Angolan cinema in our theaters, but also African cinema.

Hugo: For me the real beauty of being part of this collective is also that, all of us, despite our differences, are committed to the power of movies, storytelling and all its magical elements. Our aim is to make movies, not products, which is increasingly more difficult in a time where everything is commodified either through likes or commerce. Making movies for us is not a job, it’s a way of living. We are in essence not in the movie business, but in the business of making movies. It’s our passion and desire to make films that informs the process and the how and that to me is special.

Rumley: How do you think your education at NYFA and the work you did here prepared you for a career in filmmaking?

Fradique: NYFA gave me the foundation of what it means to be an independent filmmaker. Learning how to work collectively on other classmates’ projects and at the same time experience different positions on the set was fundamental for me to be able not only to fully understand the craft and the importance of every person on set, but also l to later on have the resources to open up a production company in my home country. On top of all that, I did my one year program almost entirely on film. We only did one main digital project with a MINI DV, no REDs at the time. Everything else was in 16mm, and each gave me more confidence as a director in the beginning of my career.

Hugo: I was already in my early 30s when I made it into NYFA, so I almost missed the window to becoming a filmmaker. I’m very grateful for the two years spent there, particularly in New York, where I was able to find the confidence and tools not only to learn what filmmaking is, but also find my artistic voice. Los Angeles was different but essential in learning a more formal, business-oriented way of producing films. There, I focused more on how to write a feature within a more conventional three-act structure and developed technically on set, playing with the vocabulary of film in a way that made me a much stronger filmmaker.

Rumley: Do you have any special shout-outs to faculty or staff who really helped or inspired you?

Fradique: I have great memories of teachers like Tassos Rigopoulos and Claude Kerven. Together with my fellow classmates, they represent the best first lessons I had about filmmaking.

Hugo: Brad Sample’s capacity to analyze, deconstruct and mentor, Ben Cohen’s humor, intellect and love of film history, Rae Shaw’s production acumen stand out. Sanora Bartels, Greg Marcks, and Robert Taylor for teaching me the science of script writing. There are others I’m sure, but those stand out.

Rumley: What advice do you have for recent graduates making their way in to the professional world?

Fradique: As it became easier to have the resources to make films, also it seems more difficult with so many options to follow or trying to keep up with all the trends and gadgets. My advice would be don’t get stuck on the gear, to spend more time and make meaningful connections and partnerships with the people you work with. Watch a lot of films and think collectively, that’s the root of filmmaking. Surround yourself with people that are different from you but have the same passions, values towards art and don’t forget the best stories are found at home, wherever that might be.

Hugo: Filmmaking is a mansion with many rooms and it’s very easy to get lost wandering in it, figure out what your strengths are and sink into what and who you are. By that I mean, what do you bring to a story, a set, a crew, a production company? What are you making films for? If you’re able to answer that, regardless of success or failure, you will find the nourishment you need to carry on.

Rumley: These are trying times in the world today, and art matters more than ever. Do you want to share any words about the importance of film in the lives of humans living right now? The role of Angolan film in world cinema?

Fradique: The world we have today is the result of the same and single story being told for centuries. We need more diversity behind the cameras and in what see on the screen. We need to remember that culture, art, is not mere entertainment or something to disconnect us from our daily life online. Be aware not only of your country’s borders, but your social and society borders as well. Cinema is more than a mirror; it is art and memory with all the senses, feelings and its lapses. Let’s take care of our memories.

Hugo: At its core, film is still the only art form that explores what it means to be human. It’s not the imitation of life, it is the imagination of everything life could be. In a time when the very existence of organized human life is at stake, we have to make sure, now more than ever, that the films we’re making get to the core of that exploration. There is a war raging that isn’t new, one that is fought between commerce and the full potential of film as an art form. It’s an age-old battle, where there will always be those who will try to define films as a monolith, by creating markets and monopolies where the overarching definition and structure of a film is the same and where its success is only measured by if it won anything in a festival or how much money it made vs. the whole history of the art form, where the writers, directors and producers made a film because they wanted to birth something that was urgent, as a way of life, as means of catharsis, beyond conventions of class or structure. Filmmakers have made the history, inside big studios or the smallest of spaces, with the biggest crews and the most skeletal ones, by understanding and studying film history and the art form. Angola is a young country and is showing potential to create both types of films, both profit-driven ones and ones that channel and respect the history of film as an art form. We champion the latter.

Rumley: Anything else that you would like to say to the NYFA community?

Fradique: Be safe and be informed. If you have the chance, watch Air Conditioner at We Are One: A Global Film Festival starting June 6th.

Hugo: Please watch Air Conditioner here: https://youtu.be/cfEWfx9RMLQ and donate if you can. Every dollar counts.

Rumley: Congratulations! We wish you the best with your We Are One screening and in all your endeavors. Keep making art; keep telling your stories. They matter.

New York Film Academy would like to thank Fradique and Hugo Salvaterra for taking the time to speak about their new film, Air Conditioner, and congratulates them on the premiere of their film at the We Are One Film Festival.

UPDATE June 19, 2020: Fresh off their screening with the We Are One Global Film Festival, Fradique and members of his crew and production company, Geração 80, will join Crickett Rumley, NYFA’s Director of Film Festivals, for a discussion of their film Air Conditioner on June 25, 2020.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2crYKgRbpRI&list=PLXZorT0OiFFZiU8AS8pmcAlhahPhggJhx&index=2