Just as a comedian has the ability to see humor in every day scenarios, a cinematographer is able to see hidden beauty and storytelling elements in a scene. It’s an art form like any other and shares a number of skill sets common to conventional photography, and developing what’s known as the “cinematographer’s eye” is practically essential when it comes to taking your movie projects to the next level.

How to be a Better Cinematographer

Cinematography is a skill that can be learned and improved upon, no matter what your current level of experience. If you want to grow in leaps and bounds, here are five essential things you should study in order to advance your craft.

1. Study Silent Film

When you’ve only got visuals to work with, you’d better make sure your visuals are damned good.

That’s precisely why the silent film era is a great go-to source for examples of how filmmakers got the most out of their cinematography rather than using it as an afterthought. A fine place to start would be with G.W. Pabst (who we’ve analyzed previously), but here are a few more that are worth delving into:

- Charlie Chaplin (obviously)

- D.W. Griffith

- King Vidor

- Erich Von Stroheim

- Cecil DeMille

- Fritz Lang

- F.W. Murnau

In fact, try making a silent short yourself – it doesn’t have to be anything elaborate, but tying your right hand behind your back is a surefire way to develop a killer left hook.

2. Study Cinematography

Sounds obvious, right? If you want to get good at cinematography, you should study the craft of cinematography. Unfortunately, it’s something that many filmmakers—both professionals and hobbyists—either put on the back burner or, worse, ignore entirely.

There’s nothing wrong with learning by doing or picking up experience out in the field, but couple this time spent at an intensive cinematography school, and you’ll be able to get deeper into the subject a lot quicker. Even if you’re not actively involved in cinematography duties while on set (or it’s not something you’re looking to break into), a cinematography program can help bring you up to speed on what the cinematographer actually does, helping you to work as a much more unified team.

3. Study Your Equipment

This goes for any role in the production team, but a cinematographer in particular needs to be a jack of all trades and pretty much a master of them all, too (particularly on smaller productions in which the director and cinematographer are usually one and the same).

In particular, a good cinematographer is one who knows every single camera and piece of lighting equipment on set, inside and out. Your job will be to translate the thoughts and instructions of the director—which might not necessarily be overly articulate—into real-life results. Naturally, you’ll only be able to do that effectively if you know exactly how to manipulate your tools; coaching those enlisted to help you to do the same is also paramount, so be prepared to brush up on your coaching skills while on set.

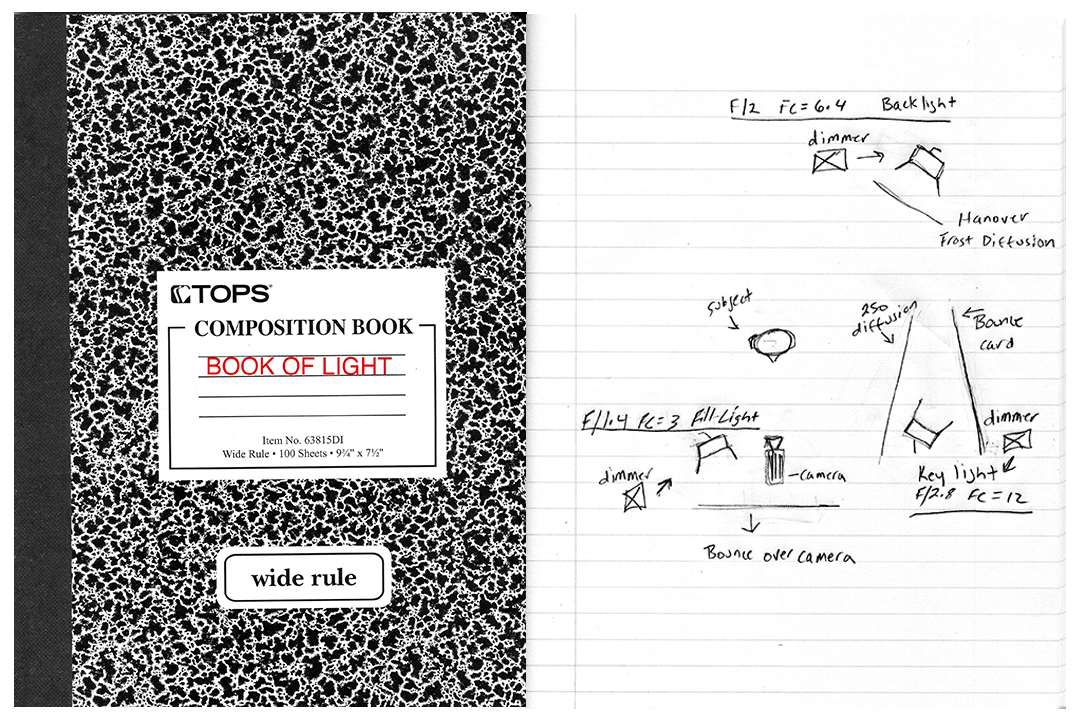

Essentially, all this boils down to skills in both communication and technology, so there’s no substitute for getting elbows-deep in theory and doing your reading. It may sound dull, but you’ll want to memorize every page of every instruction manual of every camera you’re likely to use and then put this learning into practice with every lens you can get your hands on at every chance you get.

The same goes for lighting equipment and techniques, but at the same time, don’t try and stick too close to the book either. Sounds paradoxical, but every set and situation will be different—you can’t force a square peg into a round hole, so make sure you keep a spirit of innovation and problem-solving around you at all times. You’ll be surprised at the number of techniques you’ll pick up (and possibly even invent) through experimentation.

4. Study Photography… With No Humans in It

Photographing human subjects is easy (comparatively speaking), given that there’s a definite object to frame and that the object itself is malleable by the photographer.

Take the human out of the shot, however, and it’s not immediately clear what the subject is (or should be).

That’s where the cinematographer’s eye comes in; identifying why the shot is important and needs to be taken in the first place, followed by how best to tease out all of the relevance and show it in the best light. As such, a lot of good instruction on framing and composition can be gleaned from such photography and instantly applied to filmmaking; some of the most expensive photos ever sold don’t depict living subjects, and there’s plenty of inspiration out there to draw from.

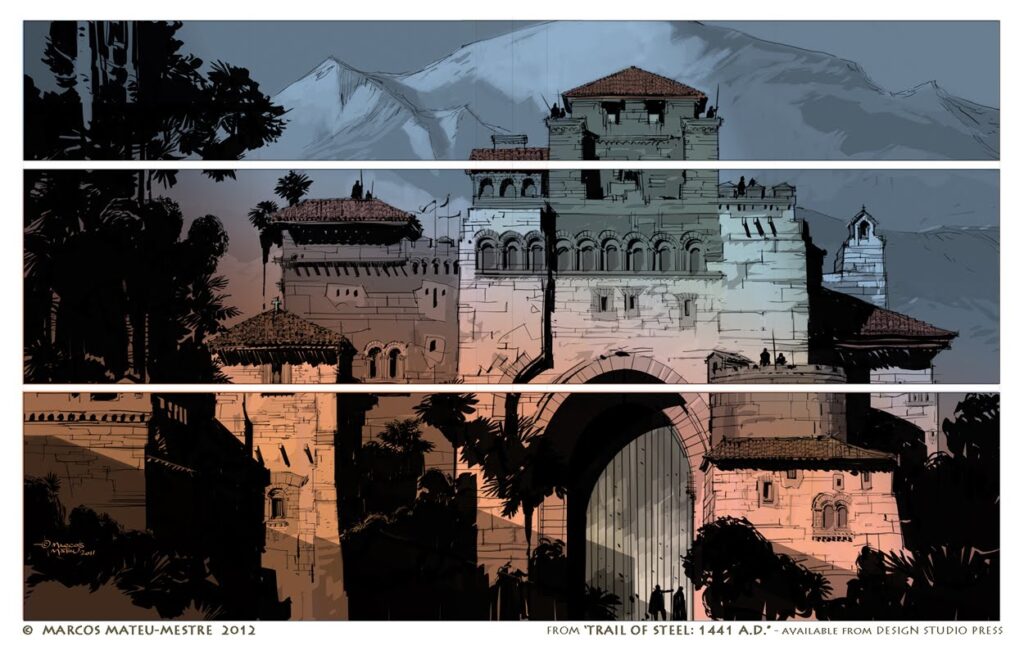

5. Study Graphic Novels

Think that comic books are a waste of time and can’t teach you how to frame a shot?

Enough said.