An image system is an image or a motif that is repeated during a film. The audience is watching it but they’re not aware of it. The image system is there, but the director hides it enough so that the audience is not really aware of what they’re looking at, unless somebody points it out.

But wait a minute … if the audience is not aware of an image system, then what difference does it make?

Aha! Great question. Well, just because an audience is not aware of an image system doesn’t mean it doesn’t affect them.

Images have the power to bypass the part of the brain that does the judging and get straight to the part that feels. This is one of the things film does very well, and an image system is one of the way in which it does it — a highly effective way. We hide the images in plain sight, so that the brain can’t analyze them and catalogue them. In that way, they affect you without filters, raw.

The image system usually reinforces a thematic concern of the film by repeating an image that has connotation for the story. Let me explain: The film “Casablanca,” for example, has an image system of prisons.

There’s an airport tower light in Casablanca that rotates like a prison guard tower light, as if it was searching for somebody. This reinforces the idea that the residents of Casablanca are prisoners in their own country.

The characters are often seen through bars, or through the shadows of bars. There are even scenes in which characters are wearing stripes.

This is all part of the design of the film, and as you watch it, you don’t really notice it. You can watch the entire film and never become aware of the image systems. (Now that I’ve pointed them out, next time you see the film, you’ll notice for sure!)

Another one of my favorite image system examples is “Michael Clayton.” In “Michael Clayton,” written and directed by Tony Gilroy, the color red represents the truth. (At least that’s what I think. I’ll have to ask Tony one of these days.) And as the tagline of the film suggests, in this story, the truth can be adjusted.

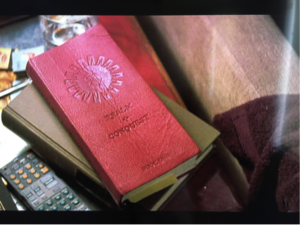

There’s a book in the film that plays an important part in the story. This is a book that the son of the protagonist is reading, that he wants his dad to read. The book has a red cover.

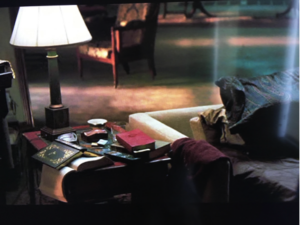

There’s a scene in which Walter, one of the main characters of the film, is talking to the woman he’s in love with on the phone. He’s wearing a red robe. She talking on a red phone. She’s talking from a room that has red wallpaper.

Right before the scene starts the director shows you an image of a farm in the winter. Most of the frame is white with snow, except for a big red barn.

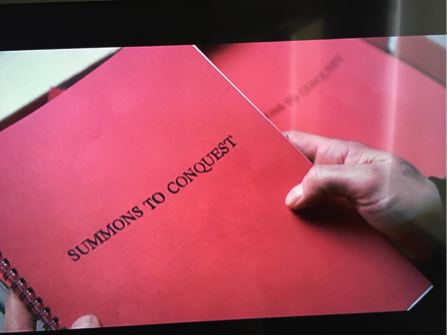

Michael, the protagonist, finds a major clue to the murder of his friend, in a document his friend had photocopied and bound. The binding of the document is red.

Inside of Walter’s fridge there’s nothing more than a bottle of champagne and some containers of red jello. The inside of the van that takes away the equipment from a failed restaurant venture Michael is trying to auction off, is red.

Over and over, the color plays an important part of the story. Mr. Gilroy masterfully inserts the image system into the fabric of the film and you’re never really aware he’s doing it.

Here’s another instance, and this might be stretching it a bit, but I’m going to go for it anyway: the protagonist’s son, the only thing true and pure in his life, is a read head.

When you’re watching the film, you don’t notice these things unless you’re looking for them, and even then, they can be so subtle it can still be hard to identify them. I sometimes play a game with my students. I tell them there’s an image system in the film. I explain to them what an image system is, but I don’t tell them what it is, and 90 percent of students can’t figure it out, even though they’re looking for it.

Once I point it out, they can see it no problem.

This is because the image system works best when you’re not aware of it, when your brain can’t edit it and interpret it. It affects you in a much more powerful way. Once I point it out then it loses most of its power: Now you can identify it as a device. (My apologies to Mr. Gilroy for spoiling the fun. His film is superb and I’m sure you’ll enjoy it, spoilers or not.)

It is the mark of the amateur filmmaker to show you the metaphor up front, to make it visible. To say, “Look, this means something!”

The pro puts the metaphor somewhere in the back, to enhance the story, but never leads with it. The story always comes first. Remember that. Story, story, story.

Still, that doesn’t mean you can have some fun with the other stuff as well.

NOTE: All production stills are the property of Warner Brothers and used here for editorial purposes only.