Essential DVDs: Paths of Glory (1957); Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964); 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968); A Clockwork Orange (1971); The Shining (1980); Full Metal Jacket (1987); Eyes Wide Shut (1999)

Oscars: Best Visual Effects (2001: A Space Odyssey)

In His Own Words: “Telling me to take a vacation from filmmaking is like telling a child to take a vacation from playing.”

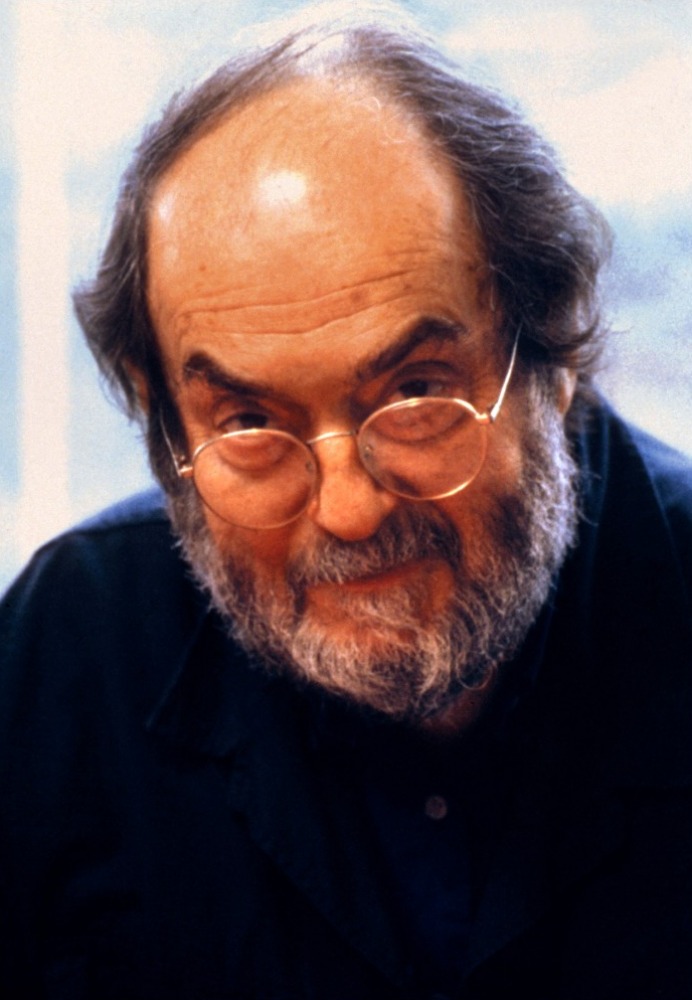

On this day, we remember the legendary and visionary filmmaker, Stanley Kubrick.

If Stanley Kubrick was still alive and had kept to his familiar stately schedule of completing a movie every six or seven years, we’d have been able to enjoy a 13th project. But though the legendary, visionary director may be gone, we have the films; 12 made in half a century of work, each radically different from the others — there was science fiction and sex, heists and horror — yet familiar themes snake through them. There are meditations on the usual big subjects: war, violence, love, sex and death but if he had overriding concerns they cluster around notions of reason and irrationality; control and chaos; of man’s attempts to corral and master the world, to impose his will, and his inevitable failures.

The theme reveals itself in his first properly “Kubrickian” movie, The Killing (he disowned both Killer’s Kiss and Spartacus, the first as an amateur, practice, piece of work, the second as a studio picture on which he was a hired hand) in which a perfectly planned heist slowly unravels with deadly and then comic results. Dr. Strangelove, Paths Of Glory and Full Metal Jacket gaze, horrified, on the phenomenon of war, not so much on its injustice and violence, but on its insane, deadly illogicality. In Dr Strangelove a plan, The Doomsday Machine, supposed to prevent the apocalypse actually precipitates it; in Paths Of Glory a general winds up ordering his troops not to fire on the enemy but on each other, while the first act of Full Metal Jacket (and its best) has R. Lee Ermey (one of only two actors ever encouraged, indeed allowed to improvise dialogue on set –the other was Peter Sellers) turning his troupe of boys into inhuman killing-machines, but the unintended consequence is that one kills his tutor, and then himself. (Shades of HAL here, a being created to be perfect turns on his creators and destroys them.) For Kubrick, a man famously devoted to order and reason, these collapse into chaos and self-contradiction provoked a ghastly fascination.

If the intellectual content of Kubrick’s films has an admirable consistency, then so do his astonishing visuals. He once compared the experience of watching a film to be near to dreaming, and dream motifs and ideas repeat, mutate and develop, symbols that slip from one film to the next. There are the hotels: The Shining’s Overlook obviously but also The Orbiter Hilton in space in 2001, and the New York hotel foyer where Alan Cumming flirts with a nervy Tom Cruise in Eyes Wide Shut. Ballrooms recur in The Shining, Eyes Wide Shut and as the scene of the court-martial in Paths Of Glory. And, of course, there are the lavatories. He had an almost mischievous love of setting vital scenes in the room that has us at our most undeniably human. Jack Torrance confronts his demons and determines to kill his wife and child in the Overlook gents. Tom Cruise begins his odyssey reviving an OD victim, who will subsequently save his life, in a luxurious Manhattan penthouse bathroom while in Full Metal Jacket (starring NYFA Board Member and Master Class Instructor Matthew Modine) Vincent D’Onofrio unleashes his fury and his rifle in a barracks latrine. It’s a version of that old tension again, the perfections and profundities of drama set against the realities of life: we all have to go to the crapper.

https://youtu.be/x9f6JaaX7Wg

No other director has had such a sure technical grasp of the mechanics of filmmaking: the lenses and film stocks; the cameras and contraptions. He pushed the technical envelope with almost every movie he made: he shot by candle-light in Barry Lyndon; he pioneered the now overused Steadicam in The Shining while his last film, Eyes Wide Shut gains its hallucinatory luminousness from his daring, borderline crazy decision to “push-process” the entire movie, a dangerous strategy, usually only used in emergencies since the slightest miss-timing can destroy the negative. But Kubrick managed to marry this technical virtuosity to an almost spiritual understanding of cinema’s intangibles: the relationship of images to our subconscious; the feelings and attitudes that can be provoked by space, colour and movement –the things that make cinema a uniquely potent art form. 2001: A Space Odyssey is as near to a purely visual experience as cinema gets. What dialogue there is is deliberately banal and unhelpful, but the imagery: bones transforming to bomb platforms; a ballet in orbit performed entirely by spaceships; Bowman bathed in HAL’s amniotic-red light as he performs, in the film’s most ironically emotional scene, the termination of a machine, are unforgettable. They communicate more potently than words.

Red, in fact, forms another of Kubrick’s repeating motifs, it gushes out of elevators in The Shining, signals decadence and danger as the scarlet carpet in Eyes Wide Shut, it’s the colour of the typewriter that looms in shot at the house of Alex’s rape victim in A Clockwork Orange and her fetishistically ripped jump-suit.

He didn’t live to see critics tear into his last masterpiece Eyes Wide Shut though he may have been aware of them arming themselves during the dimwit hysteria that surrounded its filming. (None of his films received unalloyed praise immediately, but most were subject to the gradual, embarrassed shifting of critical opinion in the years that followed their release.) Many publicly lamented what they saw as Kubrick’s stunt casting of Cruise and Kidman, bemoaned the film as a crass celebrity fuck-fest and were secretly disappointed when said treat didn’t materialise. In fact, it might be his finest film, synthesising the pessimism of The Shining and the glorious optimism of 2001 into a human experience both intimate and recognisable, the stresses and contradictions of sex and marriage. And it unambiguously cements Kubrick’s belief that film is akin to a dream (mind-bogglingly some critics failed to notice the theme: the clue’s in the title guys). It certainly, like all of them, bears repeated, fascinated re-watching.

In matters of mystery, Stanley Kubrick once said, never explain. His films are, as they always will be, precise, elusive, beguiling. They often seem at first glance to be alien and cold, yet later we find that they can speak to us at our most human level. Unique against the cinematic landscape, they stand like monoliths in a desert.