Essential DVDs: Blood Simple (1984), Miller’s Crossing (1990), Barton Fink (1991), The Hudsucker Proxy (1994), Fargo (1996), The Big Lebowski (1998), The Man Who Wasn’t There (2001), No Country for Old Men (2008)

Oscars: Best Screenplay (Fargo, 1997); Best Adapted Screenplay, Best Director (No Country for Old Men, 2008)

In His Own Words: “We do pander to the audience. But the audience we think about is us.”

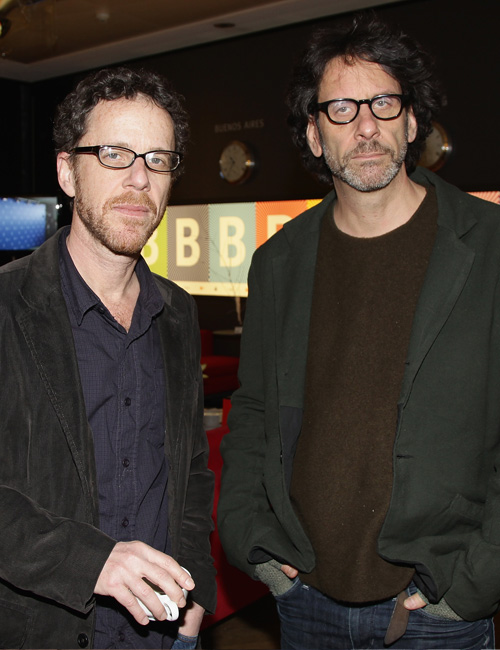

It was as dreamy teenagers one soporific 1960s Minnesota summer that Joel and Ethan Coen decided they should make a film. They cut lawns to afford a Super-8 camera, and then sat down to decide what to shoot. Finally, they filmed a movie playing on TV. Two brothers from small-town Minnesota playing with cameras, making a film of a film: a cute family snapshot, but also the crystallisation of what would become practically a modus operandi.

Raised far from the studio soundstages of Hollywood or New York’s artistic set, the Coens are all Minnesotan. How else to account for their peculiar, restless imagination than a childhood spent in a cultural backwater? Unschooled in filmmaking dogma, the brothers were nonetheless immersed in filmic tradition, lapping up noir whodunits, Ealing comedies and Sturges’ 40s satires as kids. Their films, which reverentially toy with these conventions, admits Ethan, are, “about other movies.” Blood Simple, their debut, betrayed a love affair with noir, a relationship taken to obsessional extremes with The Man Who Wasn’t There. Hudsucker Proxy’s feelgood Capra absurdities concealed a film about the Hollywood studio system. Barton Fink actually took place in Tinseltown, and The Ladykillers was a straight-out remake of the earlier classic.

Since their formative, for-fun Super-8 experience, the Coens have never stopped playing with cameras. All their films are comedies of a sort, usually the deliciously dark — and frequently surreal — kind. “We’re not trying to educate the masses,” they once agreed, and each film simply bulges with a sense of joy at the possibilities of life through a lens. The mercurial eye of their “self-conscious camera”, especially in earlier works, doesn’t merely observe a scene, but participates — the tracking shot along the bar in Blood Simple that hops over a laid-out drunk; the plentiful point-of-view perspective in Raising Arizona. The uninhibited camerawork and inventive editing becomes as integral to the comedy as any dialogue or sight gag.

Despite the fact Joel is credited as the director, the brothers share all duties, including editing (albeit under the alias Roderick Jaynes), producing and writing. And what writing it is, breathing life into a carnival of eclectic characters cast somewhere between the pitifully mundane and the hilariously grotesque. What stands out among their procession of hyper-real humanity is the love the brothers invest in even the most marginal character. Typically inhabited by a stock company of some of the most creative character actors around, vivid, larger-than-life cameos are another Coens’ hallmark (John Turturro’s Jesus Quintana in The Big Lebowski, John Goodman’s Big Dan Teague in Oh Brother…, Steve Buscemi’s Mink in Miller’s Crossing, et al). And filling these creations’ mouths is the arch, cartwheeling dialogue that betrays the brothers’ literary loves – pulp authors Raymond Chandler, Dashiel Hammet and Elmore Leonard among them.